Adding Analytics to Your v1 Product

We just checked off the last feature on our v1 list. Engineers think we can clear the bug list by Friday. Servers are provisioned. We have our emails to TechCrunch standing by in our drafts folder. Someone asks: “hey what did we decide to do for analytics?”

Without thoughtfully defined, well-instrumented analytics, we won’t know whether we’re achieving our goals. Here are my thoughts on the key decision points.

Note: this guide is vendor-agnostic. Most analytics vendors nowadays provide similar and comprehensive features to help us instrument our apps.

Ownership

The product team should own what data to collect, because it owns the goals that lead to delivering value to our users. Analytics requirements may also come from these teams:

- Engineering: needs to instrument the app for error and crash reporting to ease bug-fixing. Like features, analytics instrumentation needs to be prioritized, as some data may be easier to gather than others. Discuss whether data is available from databases or log files, which reduces instrumentation work.

- Analytics: if we’re lucky to have access to dedicated analytics resources, be sure to formulate our plan with them. They’re our day-to-day support and can help us go beyond the basics and the obvious.

- Marketing: discuss the need to run marketing campaigns or do A/B testing.

What to Measure

It’s important to gathering relevant data, not more data, especially in the beginning when we’re in a rush and cannot have 100% instrumentation coverage.

Define Goals

The first question we should ask ourselves is: what goals help us deliver value to our users? A goal for a mapping product may be: are users finding what they’re looking for inside a building?

Google Maps’ Indoor Map

We can define this goal as a user who searches for a place, zooms in close enough to see Indoor Maps and places’ names, selects a floor, taps on a place, then either visiting its website, calling it or getting directions to it. We can then instrument for the actions that lead to this goal.

Goals should be actionable. If we’re not achieving the goal of helping users find things inside a building, we can look at where in the workflow users dropped off. For example, users do not usually tap on places on an indoor map. We can iterate the product by increasing the size of place icons and their touch target, hopefully changing user behavior and increasing goal conversion.

Think in Aggregate

To deliver values to our users, we need to understand their behavior patterns, and gather data that can be aggregated across the whole user base.

Continuing with the mapping product example: data on user’s actions can be aggregated to answer questions like:

- How many users search for a shopping mall?

User’s search query is less relevant. Questions like these provide less actionable insight:

- How many users search for a specific shopping mall?

- How many users search for a location with a name that is 13 characters long?

Think as the User

Traditionally for web analytics, the basic unit of measurement is page views. For apps, we really want to understand user’s intent. We can do this by thinking about what actions users can perform at a given point in time. For example, on a chat app’s chat screen:

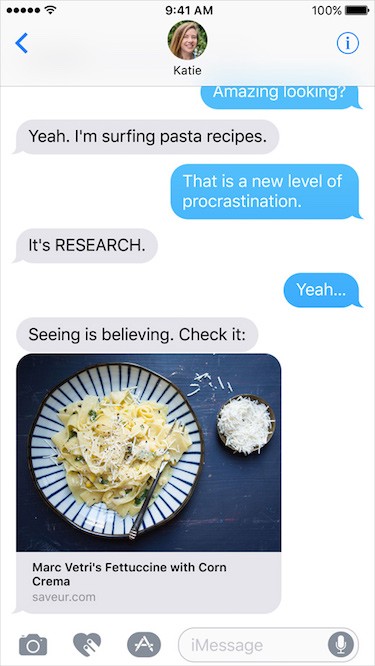

iMessage chat screen in iOS 10

We can measure these actions:

view_chatsend_message(alternatively we can increment a numeric user property or get total message count from the database)view_profileview_archive(after user scrolls above a threshold)send_mediawith propertytypeofphoto/video/audio/ etc.

How to Instrument

Name Semantically

Like in good API

design, good naming

scheme simplifies documentation and maintenance. They should be consistent,

concise and self-documenting. For example, prefer edit_comment over edt_cmt or edit_blog_post_comment. Bad naming schemes will require additional mapping layers during analysis, for example, needing to map profile_event_1 to edit_profile. Ensure there’s an agreed-upon, documented scheme and

consistently apply to all instrumentation.

Think Tags Instead of Hierarchy

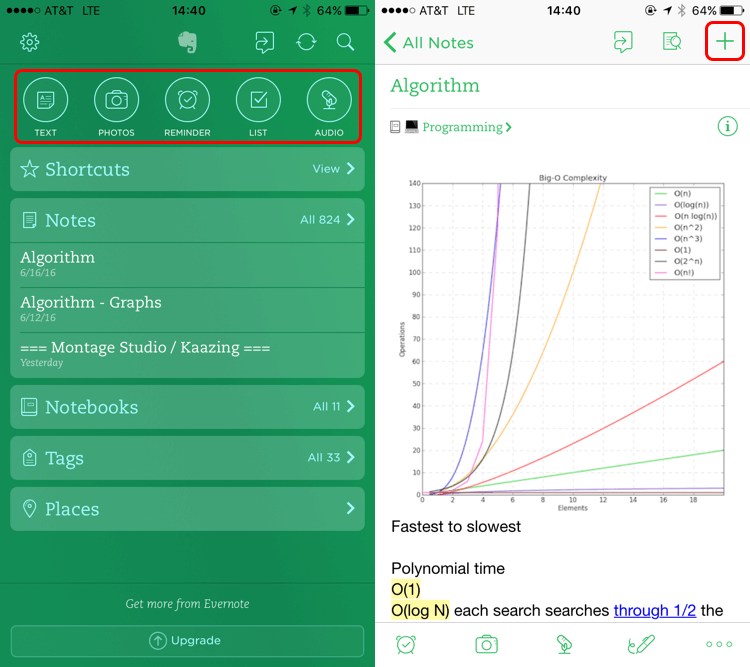

A piece of data should be atomic - describing a single, focused event, instead of a deeply nested hierarchy. This is similar to how Gmail uses labels instead of folders for better organization and discovery. For example, in a note taking app, users can add new notes from multiple screens, or even from outside the app:

Evernote’s home and note screens

Instead of instrumenting for homescreen_add_text_note and

note_screen_add_note events, we should have an add_note event with a type

property, which may be null, “text”, “photos”, etc. If we want to analyze where

users are creating notes from, we can add a source property, which may be

home_screen, note_screen, notification_widget, etc. Alternatively we can

analyze events happened before add_note, which may be view_note, view_home_screen, etc.

Instrument Multiple Apps

If we have a web app and an iOS app, we can send data to:

- 2 analytics accounts: less setup, easier to look at data separately. If we want to see data across the whole ecosystem, we have to run queries for multiple accounts then add them together.

- 1 analytics account: tag our data with the app

name

(say

webormobile). Ensure property names in multiple apps are consistent (don’t sendadd_postin one app andpost_addin another). We can see data across apps easily, but we have to do a little work to see data from individual apps, such as by using filtered views, or by running a query like “show me the number of attempts to add posts in the web app).

Separate Instrumentation from Implementation

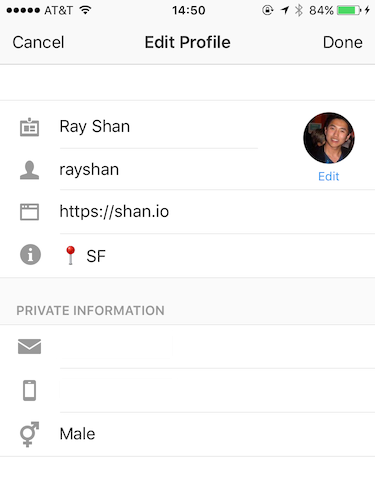

Instagram’s Edit Profile screen

Let’s say we’re instrumenting a screen that lets users edit their profile. We

should send the event edit_profile to the server when user taps on the button

that leads to this screen, as it indicates user’s intent to edit their profile.

Whether the screen loads, user abandons editing, or new profile data saves to

the server, is irrelevant to user’s intent. If we want to measure the save

action, we can send edited_profile event to the server when user taps Done, or pull the number of times profiles are edited from the database.

Document Everything

Our team will thank us even just a month down the road. I created a simple template to kick-start the process. Here are some key items:

- Property / screen / event names

- Scope of properties; for example, are properties sent for the entire app, for each user, or for a specific event

- Version and date when property was added / edited / deprecated (data should never be deleted)

Like engineering, analytics is an iterative process. Instrument our product to answer our top burning questions, but don’t sweat it if we don’t have 100% coverage at the start. We will figure out what’s missing as we analyze the data and talk to our customers to validate our hypothesis.

Thanks to Grace Wang and Shirley Xian for reading drafts of this article.

I'd love to hear what you think about this essay. Your feedback makes my work better. You can chat with me on Twitter and Hacker News .