The Camera That Takes Your Favorite Photos

A framework for evaluating street and travel photography gear

I get asked about the camera I use all the time. People are shocked that my work is shot on a camera that doesn’t even zoom. I thought I’d write down my thoughts on a framework to assess which camera will take my favorite photos.

- Who This Guide Is For

- The Framework

- Deep Dive - Usability

- Deep Dive - Versatility

- What’s Not Important

- Summary - How Cameras Form Factors Rank On The Matrix

- Further Reading

Who This Guide Is For

This is a good read for you if:

- You want something with more quality and reach than your smartphone, and you wonder how fancy of a camera you should get.

- You have a full frame DSLR and a bag of f/2 lenses, and you’re not happy with your output versus top Instagramers shooting only with iPhones.

- You’d like to turn slices of life into your favorite photos.

I went through all these phases in my photography journey. With more experience, my point of view on gear changed substantially. My framework will help you find the camera that takes your favorite photos.

This guide is not for you if you get paid to shoot something very specific, like weddings. Or you need a gear checklist for multi-party shoots and photography expeditions. If this is you, get the best camera that meets your needs.

The Framework

It is an illusion that photos are made with the camera… they are made with the eye, heart and head.

― Henri Cartier-Bresson

My favorite photos are the ones that are worthy of being on the wall, so I optimize for quality instead of quantity, and I optimize for opportunities that will get me high quality photos. To me, quality means artistic value. I am not obsessed with technical features and don’t pixel peep. Some of the most timeless photographs are not sharp.

Because I’m not a full-time pro, I also optimize for having a single camera to capture 80% of the moments I encounter. No camera can capture everything properly. Frankly if there is one, I wouldn’t want to carry it around. For camera systems, I also limit the lenses and accessories I own.

I went from a cabinet full of cameras and lenses to having all my gear fit in this photo. Some may call it a downgrade, but it drastically improved my output because I can carry it anywhere.

I assess cameras in 2 dimensions:

Usability

Some of my favorite photos just happen to me. Others I have to seek out. The camera that takes my favorite photos needs to go with me from the subway station to the top of the mountain, and be usable in all those situations. The Usability dimension focuses on answering these questions:

- Can the camera be with me everyday and everywhere?

- Will I want to bring the camera? Will I want to take it out of the backpack?

- Will I be able to capture the moment when I see it with my eyes?

Versatility

The Versatility dimension overlaps with the Usability dimension to answer:

- Will I be able to capture the moment when I see it with my eyes?

The camera’s technical capabilities fall under this dimension. Because I optimize for having a single camera, it needs to be technically strong enough to be versatile in a large variety of situations.

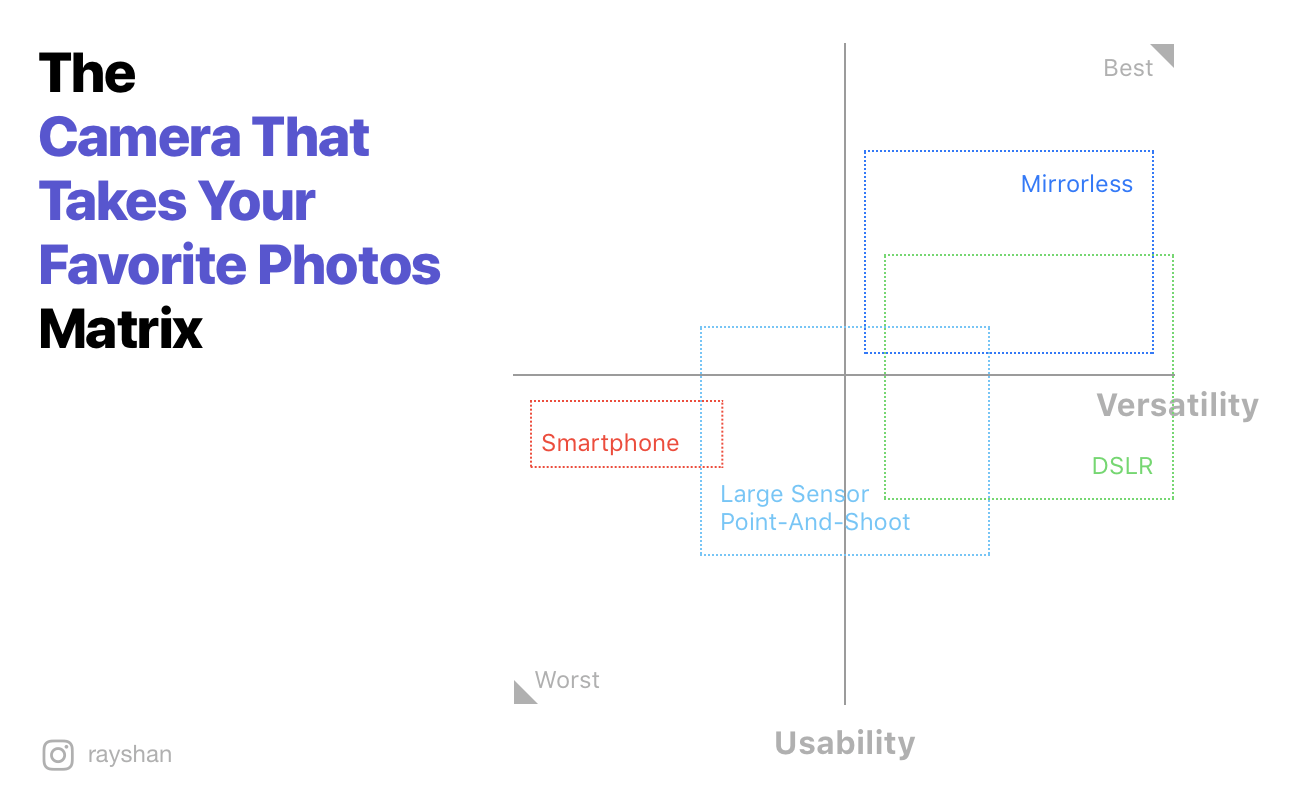

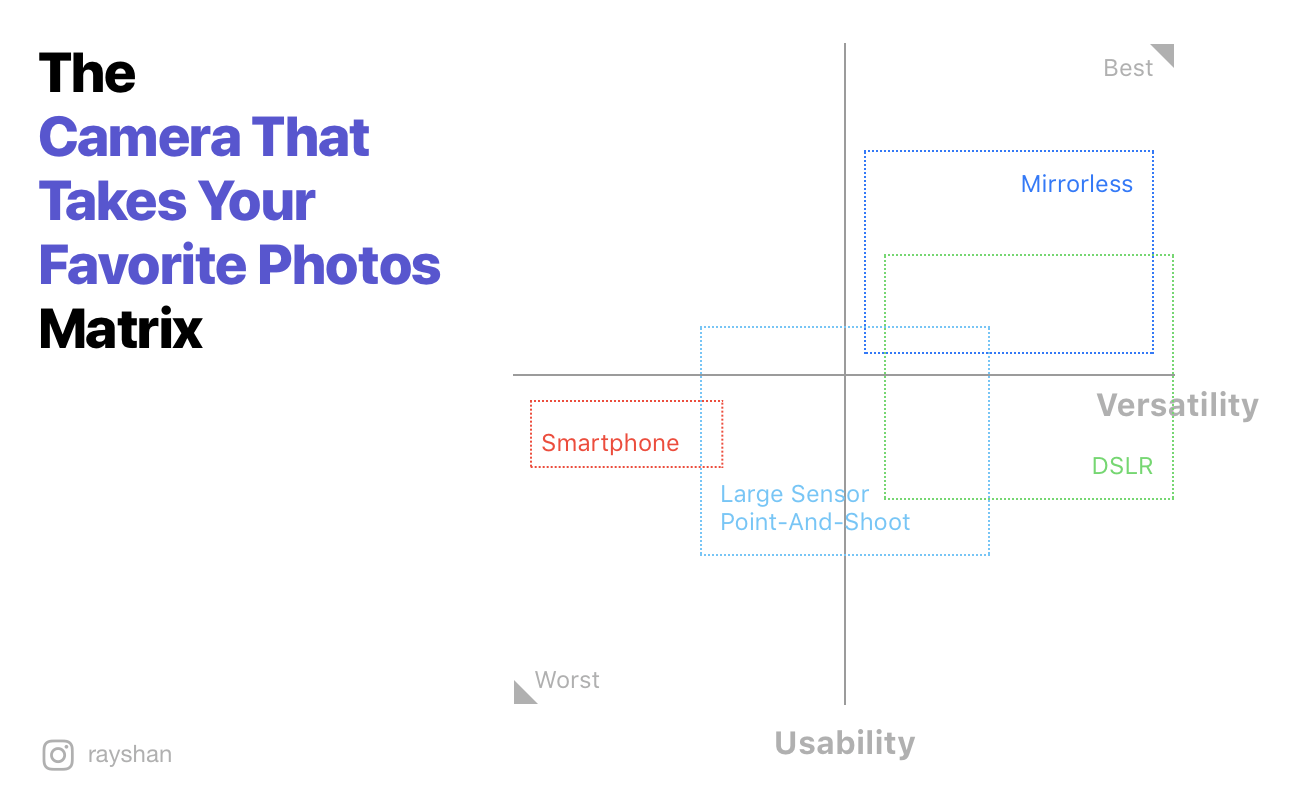

The Usability and Versatility dimensions make up what I call the The Camera That Takes Your Favorite Photos Matrix:

Usability and Versatility dimensions make up The Camera That Takes Your Favorite Photos Matrix.

Let’s dive deeper in the specifics of what makes a camera usable and versatile:

Deep Dive - Usability

Carry Convenience

The best camera is the one that’s with you. All of Flickr’s most popular cameras are iPhones, with almost an order of magnitude more daily active users than the next “pro” camera. Even though smartphones score low on the versatility dimension, they still take many people’s favorite photos because they’re easy to carry and easy to use. Smartphones can even capture magazine-worthy photographs, like this Times cover. My own favorite work is shot on an iPhone 6.

are iPhones.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/flickr-most-popular-cameras-apple-iphones-january-2019.png)

All of Flickr’s most popular cameras are iPhones.

Over the past 10 years, I’ve carried a camera with me almost every single day. A camera that takes my favorite photos needs to fit all my carry methods. This also means I can make every trip a photography trip. I live in an urban environment, so I typically carry a backpack at home and traveling. I’m able to lug a lot of gear with me, but I don’t want to. To decisively capture moments on the street, it’s also important that the camera is by my hand instead of in my bag. Here’s how I usually carry my camera:

- In a medium-sized backpack, up to 12 hours a day

- Clipped to my body with something like the Peak Design Capture, and not weigh me down after hours of walking / hiking

- On my hand with a wrist strap for hours

- Nice-to-have: in my pocket

I love large sensor point-and-shoots for how tiny they are. A Sony RX100 VI clipped to the backpack strap using the Peak Design Capture can barely be felt.

Smartphones and large sensor point-and-shoots score the highest in carry convenience. When a camera fits in my pocket, I no longer have an excuse to leave it at home. Mirrorless with APS-C and Micro Four Thirds sensors also shine. Their smaller bodies are nice, but the substantially smaller lenses make a bigger difference, especially when I need long focal lengths for sports and wildlife. I owned a lot of DSLR gear like the famed Canon EF 70-200mm f/2.8L. Sure it’s technically impressive, but I did not take a single favorite photo with it. I dreaded lugging that 3 lbs brick taking up a third of my backpack.

💡 Pro tip: visualize what you’re willing to carry with Camera Size. It’s easy to compare cameras, even with lenses.

gives you a sense of carry convenience between 4 form factors and 24-70mm lenses.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/camera-form-factor-size-comparison-dslr-aps-c-micro-four-thirds-point-and-shoot-with-lens.jpg)

DSLR · APS-C · Micro Four Thirds · Large sensor point-and-shoot

Camera Size gives you a sense of carry convenience between 4 form factors and 24-70mm lenses.

Ergonomics and Intuitiveness

The best way I can describe ergonomics is the ability to “gel” with the camera body. I need to develop trust with the physical controls, so I can shoot decisively in time sensitive, chaotic situations. I cannot afford to fumble with buttons when my subject is walking pass me. A viewfinder, comfortable grip, and tactile, customizable, properly-spaced dials and buttons provide the most comfortable and intuitive user experience.

Experience with the camera can offset bad ergonomics and intuitiveness somewhat. The longest daily-carry I owned is the Sony RX1. It has no grip, no viewfinder and mushy buttons. But it scores highly in other areas thanks to its full-frame sensor in a compact body, and an amazing lens. I liked the overall package enough to powered through its terrible ergonomics. After years of use, I’m able to use it in single-handedly in pitch black.

Ergonomics and intuitiveness are the downfall for smartphones and large sensor point-and-shoots. I shot many of my favorite photos with them, but I cannot consistently do so, and frankly I don’t enjoy fighting against the camera. See my upcoming review of the Sony RX100 VI for more details.

Deep Dive - Versatility

Reach (Focal Length)

Street Photography

There are 2 approaches: go with a fixed focal length prime, or go with a general purpose zoom.

My preferred approach is to go with a 35mm prime. Street photography masters like Henri Cartier-Bresson built their entire careers on 35mm and 50mm because these focal lengths resemble the human eye. I created some of my proudest work with the 35mm. I like to optimize for light and composition. Most of the real estate is reserved for non-human elements. I find 50mm to be a little tight for my style. If you shoot a lot of candid photography and portraits, go with the 50mm. The biggest advantage of the single-focal-length approach is that it removes 1 variable out of the decision making, and allows me to focus on everything else that makes a photo. Prime lenses also have great low light performance. The downside is that I’ve lost many shots I composed in my head but couldn’t capture because I didn’t have the reach. And “zooming with your feet” is not a replacement for longer focal lengths due to compression distortion.

A good example of a decisive moment seen by the human eye, captured with a 35mm lens.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/disciple-35mm-example.jpg)

Disciple. A good example of a decisive moment seen by the human eye, captured with a 35mm lens.

For smartphones, always pay extra for multiple cameras with different focal lengths, such as the iPhone XS with its dual 26mm and 52mm lenses. Having a telephoto lenses let’s me capture a lot more moments with better composition and higher resolution. It’s especially good for portraits.

The Huawei P30 Pro with its quad Leica camera, covering 16mm to 125mm. It’s like having a bag of lenses in the pocket.

The other approach is to go with a general “walk-around” focal length range. The sweet spot is 24-70mm. 24mm is great for architecture, and 70mm is great for portraits. Anything longer than 70mm with reasonable low light performance is too large and heavy as a daily carry. Sometimes I will scout out a location, compose a photo in my head, then go back with specialized gear.

Travel Photography

The best focal length for travel photography really depend on where I’m going. If I’ll be in an urban area, my street photography lens will work just fine. A 35mm prime alone can work well for landscapes. The only time I reach for a telephoto lens is when I’m shooting sports or wildlife. For those occasional uses, rent something 200mm or longer from a service like Borrow Lenses.

Shot at 68mm and 200mm with the Sony RX100 VI while standing in the same position. The salt mine is actively harvested, so I couldn't have moved closer to capture multiple perspectives.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/salinas-de-maras-diptych-multiple-focal-lengths.jpg)

Salinas de Maras Diptych. Shot at 68mm and 200mm with the Sony RX100 VI while standing in the same position. The salt mine is actively harvested, so I couldn’t have moved closer to capture multiple perspectives.

💡 Pro tip: go wide with panoramas

I often compose shots in the 2.39:1 widescreen cinema aspect ratio. But what if I have a fixed 35mm prime, and I’m too close to capture the entire scene? Easy! I just take a pano. Panos can be horizontal, vertical or in a grid. The individual photos can also be portrait or landscape to maximize the dimension I’m constrained on. I never trust what the camera’s algorithm is doing with panos. Plus most cameras don’t take panos in raw. So I take individual photos then merge them later with software like Lightroom.

One of my favorites. Stitched from 6 images shot in portrait orientation. The Elephant Mountain is too close to fit the whole skyline in 1 shot at 35mm.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/taipei-skyline-from-elephant-mountain-by-ray-shan-horizontal-panorama.jpg)

Taipei Skyline from Elephant Mountain. One of my favorites. Stitched from 6 images shot in portrait orientation. The Elephant Mountain is too close to fit the whole skyline in 1 shot at 35mm.

Low Light Performance

Sensor

Smartphone and large sensor point-and-shoots’ sensors currently don’t have good enough low light performance for dark and night shots. Even the recently released Sony RX100 VI is overly noisy above ISO 3200. At least its upper ISO can be limited, and its in-body stabilization compensates for the small sensor. Is it possible to get good shots at night with a smartphone? Sure, but it’s not easy. Optimize for lit subjects, use the flash, steady the camera and use an app with manual controls to take longer exposures.

#ShotOniPhone in almost pitch black. Exposing for the bright exit allowed me to create a sense of depth, while keeping the ISO reasonable at 2000 to control noise. The photo looks great on a Retina display, but I wouldn't print it large.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/escape-iphone-low-light-photo.jpg)

Escape. #ShotOniPhone in almost pitch black. Exposing for the bright exit allowed me to create a sense of depth, while keeping the ISO reasonable at 2000 to control noise. The photo looks great on a Retina display, but I wouldn’t print it large.

With mirrorless and DSLRs, I’ve found that any reasonably modern sensor provides good enough low light performance.

💡 Pro tip: don’t compare ISOs across cameras. Different digital camera makers define the base ISO 100 differently. With the same settings, photos come out with different brightness. A photo shot at ISO 6400 is also very close to a photo shot at ISO 100, with exposure cranked up in post-processing. Here are some discussions on how ISO is “fake” by Tony Northrup and Fstoppers. Take a few photos at ISO 6400. If the noise is reasonable, it’s good enough.

Lens

A lens needs to have wider than F4 aperture, or I’ll want to reach for a tripod at night. For telephoto lenses, a constant aperture throughout the focal length range is much easier to keep track of.

Image Stabilization

Image stabilization allows me to use a slower shutter speed, which means a lower ISO with lower noise, or a smaller aperture with sharper images. It’s super helpful for shooting handheld at night. When I bought my Canon 6D and Sony RX1, image stabilization wasn’t as commonplace, so the full-frame sensor was a bigger selling point that boosts low-light capabilities. Nowadays, from smartphones to full-frame mirrorless cameras, in-body image stabilization (IBIS) is widely available and affordable. In-lens stabilization on my favorite lens works too.

Tripods

I used to lug my travel tripod with me everywhere, even going as far as getting one that fits in my suitcase. Nowadays it’s mainly used for video and construction work. Having a tripod is helpful for long exposure, low light shots, so I usually have a Pedco UltraPod Grip in my backpack. Its velcro strap is super handy for securing to poles to achieve a composition at a certain height.

Dance, drama and song. Shot on the Sony RX1 tied to a sidewalk railing with a Pedco UltraPod Grip. Anchoring the camera allowed me to use a slower shutter speed, which means a razor-sharp, noise-free photo with cars in traffic as pretty light trails.

Autofocus

I used to think auto focus performance is crucial, and I’ve certainly missed shots because my Sony RX1’s auto focus is as sluggish as they come, especially at night. But I still managed to produce work that people love. A few things helped me live with the RX1:

- Realizing that being tack-sharp isn’t what makes a photograph great.

- I take my time.

- I don’t take a lot of portraits.

I do think auto focus performance is important for certain kind of work. Having faster autofocus to decisively capture moments is one of the reasons I moved away from the RX1.

I did not nail the focus on this one, but it's still one of my favorite decisive moments.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/the-graduate-focus.jpg)

The Graduate. I did not nail the focus on this one, but it’s still one of my favorite decisive moments.

What’s Not Important

Price

My favorite photos are worth much more than the price of the camera. Even if I’m not selling prints, the sentimental value is priceless. So I optimize for cameras that can take my favorite photos, not the money I have to part with. I’m happy to spend $1,200 for a tiny camera like the Sony RX100 VI because it let me photograph wildlife on a trip to Peru, with its 200m lens and features that rival DSLRs.

But spending more money doesn’t always result in better photos. The Leica Q is another unusual full-frame, fixed-lens mirrorless, similar to my Sony RX1. When it first came out, my friend Jason let me borrow it for a month. I gave it a serious try and decided not to buy my own. It’s not because of the $4,000 price, but rather that it doesn’t do a whole lot more than my RX1. Plus I prefer RX1’s 35mm focal length to Q’s 28mm.

💡 Pro tip: buy used, sell used. Used or sales let me buy all my gear at 25% discounts. I also recoup 50% of the cost by selling my used gear. Camera technology has gotten to a point that my gear is no longer the constraint to taking my favorite photos. My artistic vision and skills are. So I’m always happy to wait for the right deal.

Sharpness

Most modern lenses are sharp enough, just don’t buy the cheapest ones. For smartphones, go for the top of the line to bring it closer to point-and-shoot’s capability.

Depth of field (bokeh)

There’s usually an ideal camera / subject / background placement that produces bokeh with my camera. Even smartphones. Play with placements to get a sense of what your camera can do. I would care more if I’m paid to shoot portraits.

Resolution

Everyone’s making a 25-ish megapixel sensor nowadays. It’s fine, even if I need to print large 50-inch prints. Smartphone’s 12 megapixel sensors are limiting. They can still take my favorite photographs, I just have to be prepared not to crop too much or print too large. If I find myself cropping a lot, I would go with a different focal length before considering a 40 megapixel sensor body.

One of my favorites. An extreme crop from a 24 megapixel image shot on the Sony RX1.](https://shan.io/assets/img/camera-matrix/gate-by-ray-shan-crop-from-original.jpg)

Gate. One of my favorites. An extreme crop from a 24 megapixel image shot on the Sony RX1.

Dynamic range

Modern sensors are good enough. Learn to properly expose shots so you don’t need to recover that much highlight and shadow details.

Summary - How Cameras Form Factors Rank On The Matrix

Based on the Usability / Versatility dimensions and criteria, here’s how the different camera form factors rank on the Camera That Takes Your Favorite Photos Matrix:

How different camera form factors stacks up against each other on the Camera That Takes Your Favorite Photos Matrix.

Mirrorless - this is my form factor of choice. It’s easy to see why mirrorless is winning against DSLRs. The versatility is just as good, and they’re easier to carry. Mirrorless also has much better ergonomics and intuitive user experience than large sensor point-and-shoots. Even if they’re not pocketable, I value their ergonomics more, so I rank them higher in the Usability dimension.

Large sensor point-and-shoot - this is the form factor I recommend to someone with a smartphone and wanting to capture more favorite photos. It’s versatility makes it a worthy upgrade from smartphones, and it’s easier to get started with than mirrorless. Smartphones’ carry convenience do make them great backup cameras.

Not considered

Medium format - because I’m not a pro, full-frame is as big as I’d go. I don’t want to lug that much gear with me and pay multiple times for the specialized, limited lens selection.

Small sensor point-and-shoot - modern smartphones have great cameras that zoom. I’d either stick with my smartphone, or go for something with 1” or larger sensors, such as the Sony RX100 series and the Fujifilm X100 series.

Further Reading

- The Pro Photographer, Cheap Camera Challenge series that inspired me to think outside the gear box.

- Tony Britton’s beautiful work taken with bridge cameras like Sony RX10 III and Canon SX50.

- To see how I use the Camera That Takes Your Favorite Photos matrix to assess specific cameras, check out my upcoming review of the Sony RX100 VI.

Thanks to Polina Leonova, Jon Sry and Eric James for their feedback on this piece.

I'd love to hear what you think about this essay. Your feedback makes my work better. You can chat with me on Twitter and Hacker News .